What is Restorative Justice and what are Restorative Practices?

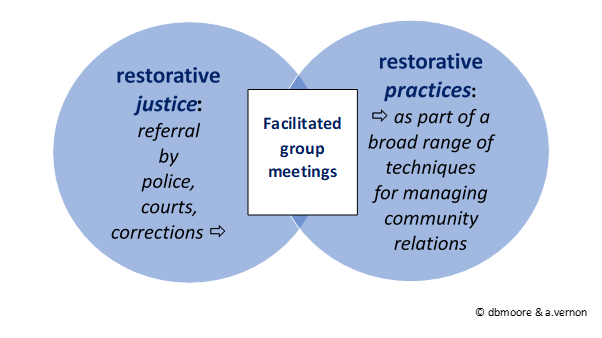

Restorative justice and restorative practices are related and overlapping approaches to dealing with social harm and promoting well-being. Both use facilitated, structured processes to help a group of people address social harm and reset relations:

The foundational principles of a restorative approach are to: cause no further harm; work with those involved, and set relations right.

We find it useful to use the term restorative justice specifically for applications of these principles in the justice system.

Restorative justice is sometimes defined by what it is not: Restorative justice is an alternative to retributive justice.

Retributive justice is a foundational element of modern criminal justice systems. Its core idea is that the main official response to crime should be retribution, in the form of punishment proportional to the offence. Retributive justice requires authorities to respond to crime with punishment in order to:

- maintain social order (by providing a routine, predictable response);

- restore moral balance (by compelling anyone who commits a crime to “repay their debt to society”);

- promote individual deterrence (by teaching a lesson to the person who has committed the crime);

- promote collective deterrence (by signalling to other potential offenders that this type of crime attracts this sort of punishment).

Maintaining social order, restoring moral balance, and promoting individual- and collective deterrence are all legitimate outcomes. However, there are other ways to achieve these outcomes. Relying primarily on punishment to restore more balance and teach lessons can be ineffectual, even counterproductive. And authorities focussed primarily on punishment can tend to neglect the needs of victims of crime.

In contrast to retributive justice, the core ideas of restorative justice are that:

- because

crime causes harm,

a core requirement of justice should be to repair that harm; - the people most immediately affected should be supported in their search for reparation, &

- members of a broader community (including professionals)

may also participate in that search.

Crime leaves a legacy of social harm, such that people affected are not at peace with themselves, nor with others. Emotional conflict typically persists:

- within

individuals, - between

individuals, - within

groups, &/or - between

groups…

… even after there is no longer any dispute about the basic facts of the case.

In criminal justice system applications, a restorative process typically addresses this emotional conflict and other harm resulting from an incident. A carefully prepared and structured facilitated restorative process can support the people affected &/or involved to transform conflict into cooperation. The most common generic name for this restorative process is group conferencing. Group conferencing provides a particular sequence of stages through which those involved can reach:

- A COMMON UNDERSTANDING, by answering: “What happened, and how has each of us been affected?”

- AN AGREEMENT ON NEXT STEPS, by answering: “What now needs to be done to repair harm, reduce the risk of further harm, promote well-being (& so set relations right)?”

Restorative justice holds that an official response to crime should not only (i) respond to the specific incident and the harm it has caused. An official response should also work to (ii) prevent harmful behaviour from recurring, and (iii) promote the wellbeing of those affected. This work of responding to something bad, preventing something else bad from happening, and promoting something good, typically requires that an intervention effect some sort of “restoring right relations”, or “re-setting relations” within the community of people affected by the harm.

This idea of restoring right relations has tended to be over-simplified. A simplistic understanding of restorative justice has been that someone who has caused harm

(i) expresses remorse to those they have harmed, then

(ii) receives forgiveness, after which

(iii) those most affected can make up and move on.

But life is not that simple, nor is restorative justice – let alone restorative practices.

For a start, restorative justice involves several distinct elements. It involves (i) some foundational principles which inform (ii) the design of administrative programs, which deliver (iii) a facilitated process, or series of processes.

Again, the foundational principles common across effective restorative programs are:

- Cause

no further harm; - Work with those involved;

- Set

relations right.

In the criminal justice system, restorative programs realise these principles by delivering appropriate facilitated, structured processes to support:

DIVERSION: Whereby police or other justice professionals refer a case to a restorative process or some other service that assists to reset right relations, and that process or engagement functions as an alternative to court or to aid the court in decision-making; OR

SENTENCING SUPPORT: A court refers a case to a restorative process after a determination of guilt. Participants in the restorative process reach some form of agreement. That agreement is then returned to the court, and is taken into account during the sentencing process.

In this application, the restorative process functions as an adjunct to court;

This application of group conferencing remains far more common in youth justice than in adult justice

&/OR

POST-SENTENCING or PRE-RELEASE HEALING: The community of people affected by a crime-that-has-attracted-a-custodial-sentence meet to “make sense” of their experience together. Used post-sentence or pre-release, a restorative process seems to support people to “get on with their lives”.

In each of these applications in the justice system, the people involved in the facilitated restorative justice process focus primarily on addressing the harm caused by injustice. Authorities are primarily responsible for providing a suitable process, rather than imposing an outcome. An appropriate process should enable the people involved to agree on how, in this particular case, our particular community will:

- respond to the specific harm;

- prevent further harm in general;

- promote well-being.